Vladimir: It wasn't you who came yesterday? Finally, when Godot's messenger reappears at the end of the day to once again instruct the men that Godot will arrive for them tomorrow, he has forgotten them entirely: Furthermore, later in the act, the 'abidingly self-absorbed' (Kaib, 175) and newly blind Pozzo appears not to remember the pair from the preceding day, asking 'who are you?' (Beckett, 76) when confronted with Vladimir's attempts to help him, and Estragon's attempts to rename him. Indeed, Gogo's memory is so bad that Brown comments that he actually fits all the symptoms for Alzheimer's disease, citing Beckett's fondness for imposing real illnesses onto his characters, but not explicitly telling his audience which disorders from which they suffer (Brown 19-20). Indeed, apart from Vladimir, no character remembers the events of the previous day: he exclaims that Estragon has 'forgotten everything' (Beckett, 56) including contemplating hanging themselves from the lone tree that populates the barren stage.

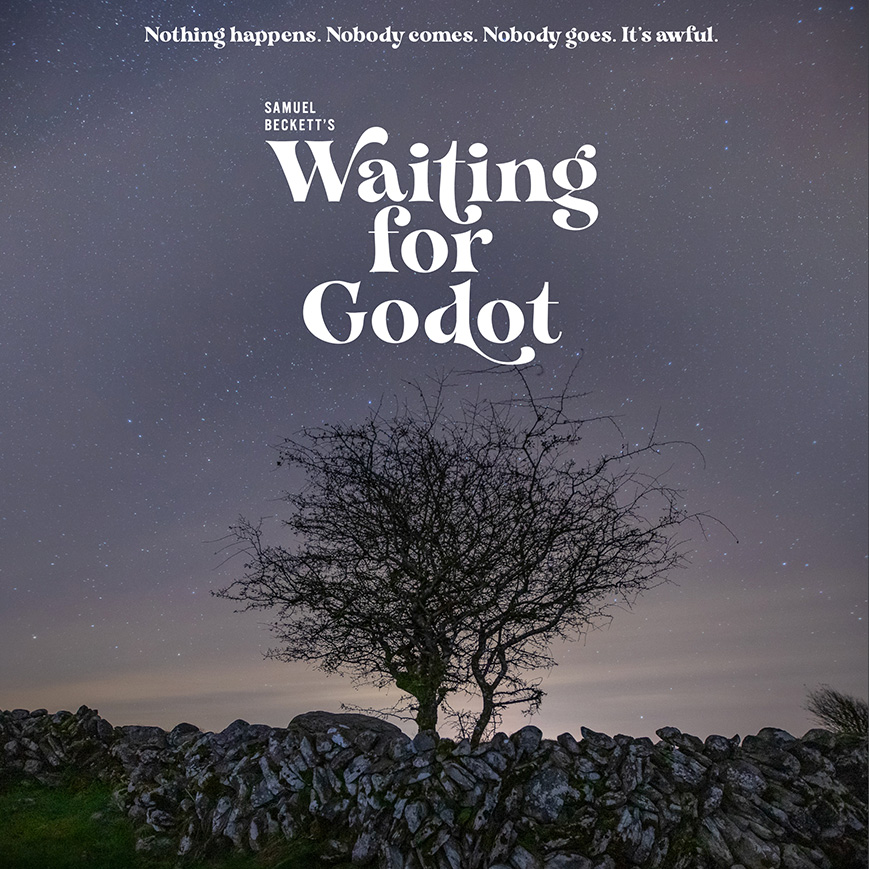

This is certainly true of Waiting for Godot, which lends itself to this idea in so far as the characters cannot remember the events of Act One during Act Two. A key feature of the absurd, therefore, is action with no distinct phases - that is to say, no obvious beginning, middle or end - but instead a play that seems to circle back on itself infinitely. Thus, playwrights occupied by the idea of absurdity were concerned with 'the human subconscious in depth, rather than trying to describe the outward appearance of human experience' (Esslin, 22) to borrow phrase from Martin Esslin. The idea of the absurd is a twentieth century philosophical movement which posits that the world is devoid of meaning or value and that it is essentially impossible to determine any overall purpose to life. Furthermore, it will question how closely Beckett's use of memory is attuned to the theatre of the absurd and how far he utilises memory in order to centre his plays in absurd worlds. As such, this discussion will focus on Beckett's treatment of memory in Waiting for Godot and Happy Days. Moreover, when analysing Beckett's absurdist tendencies, it would be foolish not to consider the merit of Happy Days (1961), a play often noted for its subscri ption to the theatre of the absurd. The play's absurdist tendencies that have been of continued interest to researchers and it is irrefutable that the human memory was of interest to Beckett - Brown notes that 'the functioning of memory fascinated Samuel Beckett throughout his long life' (Brown, 8) - so it makes sense to examine these two aspects of Waiting for Godot side by side. dauntingly challenging plays of the last century' (Seagar, 120). Alvarez as 'forbiddingly difficult and certainly becoming more difficult' (Alvarez, 23) and by Jane Seagar as 'one of the most. Waiting for Godot has, for many years, been the subject of fierce academic investigation and debate, being labelled by A. A novelist, poet, director and dramatist, Beckett was arguably most famous for his absurdist, nihilist plays, which attracted popular acclaim and sparked an uncommon amount of criticism, but none more so than 1953's Waiting for Godot, a translation of his French tragicomedy En attendant Godot.

Being a key component of what it is to be human it is hardly surprising that over the past century countless playwrights have utilised the concept of memory to substantialise their own views on humanity itself, but perhaps none have done so quite like Samuel Beckett. It frames and alters our comprehension of the human experience it defines our understanding of time itself. Memory is fundamentally the ability to recall and reinterpret the events of one's past.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)